Featured artwork,

Within Grasp, by Jacelyn Yap

|

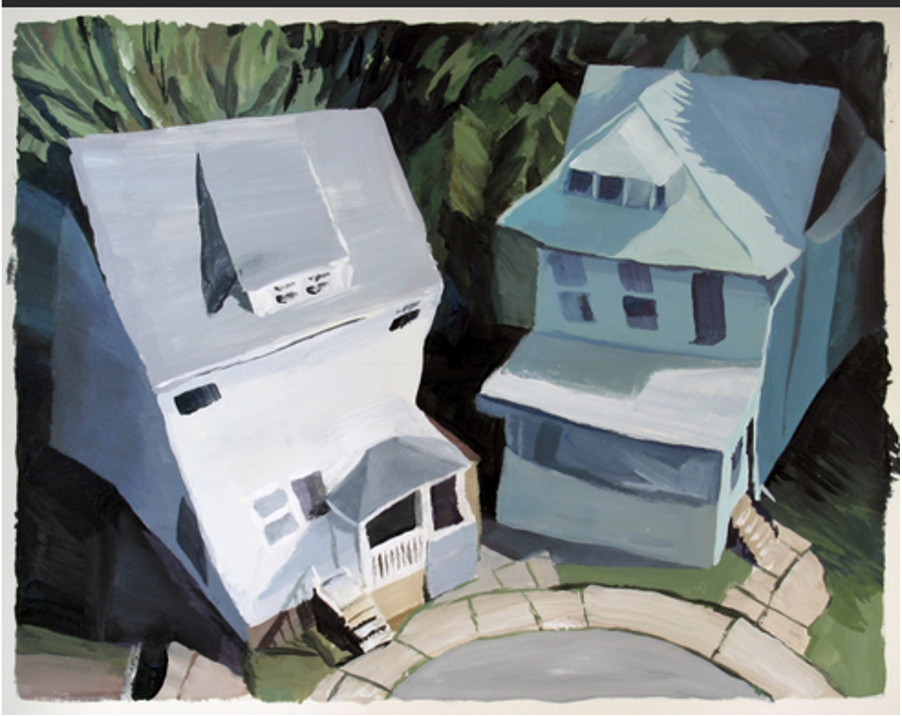

Kat Meads (text) Philip Rosenthal (art) Disturbed Houses

Nothing happened suddenly. The blackening was incremental, a creeping phenomenon. From the inside, what started as an ordinary gloomy room, too few windows, too darkly painted, grew dimmer, as if the space had decided, by degrees, to blank itself out. The resident family adjusted, as families do—unless they don’t. Unless the fallout of the once-present-now-withdrawing feels so severe, so estranging, to the family unit its members turn on one another, desperate to assign blame. Blame, in this case, for a room in retreat. An imploding family in a disappearing room. Now there’s a story, surely.

The dweller who sleeps in the upstairs bedroom to the right of the stoop (the outsider’s, right, not the insider’s) has no idea how long it’s been going on. Weeks? Months? Years? Only lately, throat parched, has he needed to roust himself from bed, middle of the night, to gulp a glass of water. When confronted by a Look-at-Me! moon, he followed, as anyone would, its laid-out path to the window and peered. Instead of silvery shrubs or a prowling cat, he saw neighbors—he was fairly sure they were neighbors—holding hands, encircling the house, beaming to beat the moon. When he drew the curtain farther back, a few broke the circle to wave. He realized, almost instantly, that the gathering had nothing to do with him. It was a tribute to the house itself, an admiration society paying homage. But you know the way it is with some houses: they like to tease. Drop a shingle here. Flake some paint there. Elevate the challenge. Test the attention span of grinning fools. How long does it take a house to empty a yard? Depends.  Speaking of brides. A few have lived here. With grooms, then without. A double-decker porch has always been a draw for the marrieds, existence writ as real estate. A veiled double-decker porch: even better, symbolically. As anyone and everyone has been forced to learn, making it up as one goes along is a tiring business. A house script saves effort all around. Just do what the rooms suggest. Eat. Sleep. Bathe. Go out onto the veiled porch, upper or lower. Assume you’re in a cocoon. Assume you’re bride-safe. Word of warning, though: don’t piss off the house. If faced with the choice: piss off spouse or house, piss off the spouse. Otherwise, otherwise…  Point of fact: the current residents previously lived in a totally new—foundation to rooftop—construction. Didn’t like it. For a while they stayed put, relying on a campaign of messiness, both pedestrian and ingenious in origin, to cure their dislike. Didn’t happen. And so they moved. The realtor, greedy though he was, hesitated to write up a contract at the asking price. The new/old house had mold. Asbestos. The pipes were galvanized. There were “unresolved water issues.” The required inspector advised strongly against the purchase. “Structurally unsound,” he said before explaining why in numbing detail. “No worries,” said the buyers. “We love it.” To ameliorate his guilt, the realtor suggested adding a “clear out the crap” clause. “Don’t bother,” nixed the buyers. “We’ll take care of that”—meaning: they’d leave the house and its contents precisely as found. The shredded chairs. The chipped tiles. The stained wallpaper. The wobbly banister. The cobweb clouds. The knee-high dust bunnies. The lone can of soup teetering on the edge of the highest shelf. Every morning they enjoyed their cereal at a kitchen table singed brown in the middle, one of its legs shorter than the rest. The house, they could tell, appreciated their leave-it-be attitude. A most satisfactory partnership. Most satisfactory.  Don’t play naïve. The backyard is not, nor has it ever been, front-yard equivalent. It’s behind the house. There’s a house between it and the front yard. Third in line, sister. Pulling up the rear. Shunned by mail carriers disinclined to increase their walk-about totals. Abjured by sales reps who can’t—on the face of it—seem too determined to get their foot in any door. Dumping ground for garbage bins, dog poop. Graveyard of grown-tired-of, rained-upon toys. Where disparaged smokers go to light up and escape harangues regarding their self-inflicted, impending demise. Did you know? Front yards get mown twice as often as backyards, if grass there is to be mown. Curb-appeal fanatics focus on—what else? Front yard landscape and design. Where are the backyard champions? Where are the experts who advise against buying cars the color of houses and parking said cars too, too close to the more commanding entity? Those owners could park those cars in the backyard—but do they? Never!  Comparisons are deadly. Do three windows automatically trump two? Will two windows attract fewer fliers—birds, balls and so forth? Birds? Balls? Those are the least of the problem. Every time, every time, the dweller ventures home, there it is: the other house, demanding to be noticed, demanding its due. Though perfectly aware of what will next occur, the dweller (you know who you are) is powerless to prevent the mind’s gymnastic progression. Notice, evaluate, discriminate, covet. “I’d like a porch!” “I’d like a window over the front steps!” I want, I’d like. I’d like, I want. You have a damn house and still you’re dissatisfied. Whatever will become of you?  It’s the weather, they said. (Pundit identities undisclosed.) Not extreme weather: not a funnel cloud spinning its destruction or a cresting flood or months of frying heat or a hideously heavy snowpack. Just average, everyday, constantly-in-play weather. The house has tried to stand up to the onslaught, is trying still—so, please, show some compassion. It’s doing its utmost to honor its directive, providing shelter to those within, even the blinkered father who has spent a lifetime denying deviation of any sort and now presses his young children to adhere to the adage: nothing changes. (Imagine! Peddling that absurdity to stretching, widening, teeth dropping, motherless children.) Secretly, the children feel the house, if it wants, has a right to be other than it’s been. Poor, dear things. They don’t understand. It’s not the house’s choice to be at the mercy of weather. Unlike their missing mother, the house can’t run away, save itself. It just can’t. Kat Meads is the author of more than twenty books of poetry and prose, including the flash fiction collection Little Pockets of Alarm. Her short fiction and indeterminate prose have appeared in Your Impossible Voice, Hotel Amerika, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Fairy Tale Review and elsewhere. She lives in California.

Philip Rosenthal has shown his paintings in New York, Boston, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles and San Francisco. He has been awarded six California Arts Council grants and has been an artist in residence at Yaddo and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. He lives and works in California. Website: www.philiprosenthalpaintings.com. |